Editor's Notes Editor's Notes

When Systems Corrupt Good People

By Chuck Armsbury, Senior Editor

Lately, I've been studying why good and

normal people sometimes do bad things. Like those ordinary Columbine

high schoolers on 4/20 in 1999 who went bowling in the morning

before killing fellow students and themselves in the afternoon.

For example, the nice kid you know from your small town who joined

the Marines, and who now kicks in Iraqi doors and shoots women

and children, or the prison guards who go to church on Sunday

and kick prisoners' butts during the week.

Revelations of Abu Ghraib torture represent

very well this ages-old dilemma. "The Christian in me says

it's wrong, but the corrections officer in me says, 'I love to

make a grown man piss himself,'" said Specialist Charles

Graner as reported on BBC News in spring 2005. Employed

previously as a prison guard in the US, Graner is the Abu Ghraib

military policeman shown smiling and having fun next to a pile

of naked Iraqis in widely circulated photos.

What was it about the inner sanctum of

Abu Ghraib, Saddam Hussein's former dungeon, which brewed a nasty

concoction of power, sexual perversion and multiple counts of

torture and abuse? How did our US troops come to act like Saddam's

henchmen?

Was Graner some kind of sick sadist, a

psychopath, an undiagnosed schizoid? Do we look within the torturer's

head for answers? Or do we find those answers by a study of the

power of situations to turn nice Christians like Graner into

torturers, others into silent bystanders?

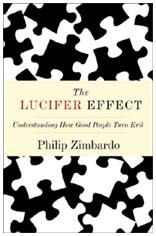

Phil Zimbardo's book

The Lucifer Effect provides answers we're looking for.

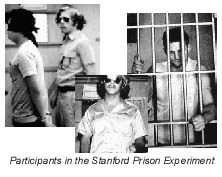

Dr. Zimbardo is the Stanford University psychology professor

who designed and supervised the August 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment

(www.prisonexp.org).

Dividing student volunteers by a coin's flip into guards or prisoners,

Zimbardo's five-day experiment produced surprising results. Mainly,

from the start these ordinary students quickly "became the

roles" they had assumed in this psychodrama. Guards dominated,

prisoners submitted. Phil Zimbardo's book

The Lucifer Effect provides answers we're looking for.

Dr. Zimbardo is the Stanford University psychology professor

who designed and supervised the August 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment

(www.prisonexp.org).

Dividing student volunteers by a coin's flip into guards or prisoners,

Zimbardo's five-day experiment produced surprising results. Mainly,

from the start these ordinary students quickly "became the

roles" they had assumed in this psychodrama. Guards dominated,

prisoners submitted.

Those who became guards by flip of a coin

began to act like real prison guards: giving senseless orders,

punishing rule violations, acting arbitrarily and manipulative.

Likewise, students playing prisoner soon adopted strategies for

dealing with their unequal power-situation. Each student for

the experiment earned daily money; each was screened for hidden

personality quirks, and several wore long hair and described

themselves as leftist radicals.

After five days that began with a 'fake'

arrest to start the experiment, to the moment Zimbardo called

it off, each of these 18 male students 'lived the roles' they

played. Particular "guards" became abusers, rule followers

or good guys; a couple "prisoners" experienced real

emotional trauma, rebels were put in the (closet) hole, and one

had to be released before five days.

The Lucifer Effect is Zimbardo's 2007 full account of the SPE. There's

a full chapter on Abu Ghraib, sections on the 1978 Jim Jones'

Guyana mass suicides, Halloween mischief and anonymity, studies

of attitudes about ridding society of social misfits, types of

dehumanization and the evil of inaction.

To dispel utter hopelessness, Zimbardo

finishes with a chapter on "Resisting Situational Influences

And Celebrating Heroism." This is a very valuable book

for social researchers and anyone wanting answers about the dynamic

interplay of personality, systems and real situations, or more

grandly, psychology and sociology.

After all, The Lucifer Effect is

about you and me. It's about who we really are, or more so, who

we think we are? Are you a Good Samaritan, or do you walk on

by that drunk lying in the gutter? Under what circumstances would

you ever intervene to stop a crime?

Zimbardo and other 'situationists' offer

convincing evidence that changing circumstances can bring out

the angel or devil in any one person, family or nation. "We"

are always "Them" to the Other. And under the power

of a wrong situation, you or I may cast aside morality, habits

of mind, principles and beliefs and "do wrong."

Unfortunately, it seems only a few of us

frail humans become heroes who resist unlawful or immoral orders,

denounce oppressive leadership or correct a teacher, doctor,

supervisor or preacher when s/he is wrong.

The language of psychology and 'psychobabble'

is found everywhere in US culture. The majority of mental health

experts teach that we "have" certain obsessions, and

that we're bipolar, schizophrenic, or depressed, and that these

sociopolitical labels are actually a medical disease, like diabetes

or measles. Drug Courts universally adopt this medical model

to describe and treat drug law offenders.

Zimbardo's lifetime achievement is demonstrating

that social reality produces these "mental" symptoms,

and that systems and social situations powerfully influence future

behavior that can trump individual will, personality traits or

religiosity.

Where lies hope within this

entrapping web of evil systems and situations? How about in a

nurturing web of a social system and culture that reinforces

cooperation, mutual respect, and equitable sharing of resources? Where lies hope within this

entrapping web of evil systems and situations? How about in a

nurturing web of a social system and culture that reinforces

cooperation, mutual respect, and equitable sharing of resources?

For more on The Lucifer Effect,

visit www.lucifereffect.com.

I'd like to receive comments and contributions

on this devilish subject.

Respectfully, Chuck Armsbury

Note: The Stanford Prison Experiment

has been optioned as an upcoming major motion picture - see www.lucifereffect.com/movie.htm

for details.

|