|

|

|

|

|

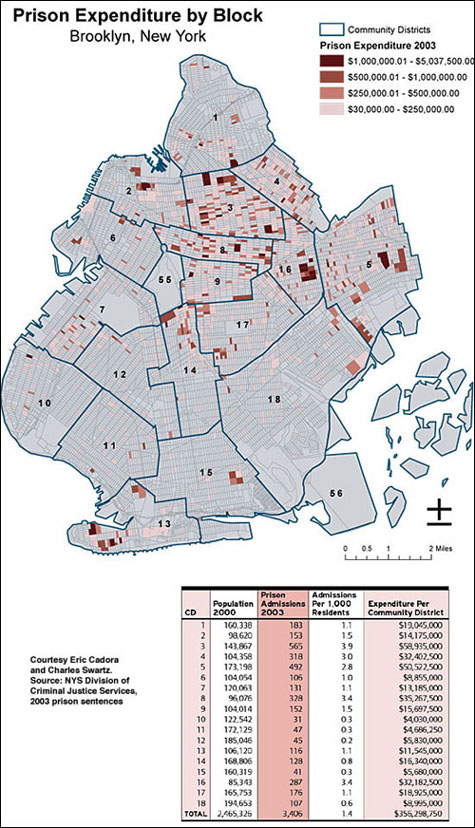

The Remeeder Houses make up one of the poorest blocks in Brooklyn. Six-story buildings rise from the rectangular patch of land between Sutter and Blake avenues, and between Georgia and Alabama avenues in East New York. More than 50 percent of the project's residents live below the poverty line. Unemployment is rampant. Run-down, overcrowded apartments are the norm. By another measure, though, this block is one of the priciest in the city. Last year, five residents were sent to state prison, at an annual cost of about $30,000 a person. The total price tag for their incarceration will exceed $1 million. Criminal-justice experts have a name for this phenomenon: "million-dollar blocks." In Brooklyn last year, there were 35 blocks that fit this category -- ones where so many residents were sent to state prison that the total cost of their incarceration will be more than $1 million. In at least one case, the price tag will actually surpass $5 million. These blocks are largely concentrated in the poorest pockets of the borough's poorest neighborhoods, including East New York, Bedford-Stuyvesant, and Brownsville. In recent years, as the U.S. prison population has soared, million-dollar blocks have popped up in cities across the country. Maps of prison spending (like the one below) suggest a new way of looking at this phenomenon, illustrating the oft ignored reality that most prisoners come from just a handful of urban neighborhoods. These maps invite numerous questions: How is the community benefiting from all the money being spent? And might there be another, better way to spend those same criminal-justice dollars? These maps have attracted attention nationwide from state legislators struggling to balance their budgets. In a few state capitols, prison-spending maps have begun to influence the dynamics of the political debate, suggesting new ways to think about crime and punishment, recidivism and reform. One state, Connecticut, has even gone so far as to change its spending priorities, taking dollars out of the prison budget and steering them toward the neighborhoods with the highest rates of incarceration. Prison-spending maps highlight the fact that money spent on million-dollar blocks winds up in another part of the state-far from the scene of the crime. In New York State, about 60 percent of prisoners come from New York City, but virtually every prison is located upstate, in rural towns and villages, places like Attica, Dannemora, and Malone. As Todd Clear, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, puts it: "People who live on Park Avenue give a lot of money to people who live in Auburn, New York, in order to watch people who live in Brooklyn for a couple of years-and send them back damaged." Most likely, nobody would now be mulling over the concept of million-dollar blocks if not for a 42-year-old Brooklynite named Eric Cadora. Back in 1998, Cadora was working at a nonprofit agency in Manhattan called the Center for Alternative Sentencing and Employment Services, or CASES. He taught himself mapping software and studied the various ways mapping was used, including by the New York City Police Department to identify crime hot spots. About crime mapping, Cadora says, "People weren't coming at it from a policy reform perspective-and the whole idea of [prisoner] re-entry and community wasn't part of the issue. Most of the issue was about getting tough." Cadora wanted to try a different approach. He decided to create a new set of maps, which he hoped "would help people envision solutions rather than just critiques." With criminal-justice data he obtained from a state agency, he embarked on his first mapping project: Brooklyn. Colleague Charles Swartz helped, and together they made a series of maps illustrating where inmates come from and how much money is spent to imprison them. "The reasons we did the money maps weren't to say, 'Gee, we spent too much money on criminal justice,' " Cadora explains. "Because what's too much? The question was to say, 'Look, you can now think of the money you're spending on incarceration and criminal justice as a pool of funds' "-that is, funds that could be spent in a different way. He adds, "What struck me, looking back at a year's worth of prison admissions, was that these were the results of a bunch of individual decisions, but it turns out to amount to enough financial investment to be thought of as an actual spending policy." In 1999, Cadora began sharing his maps with criminal-justice agencies and nonprofit organizations. Word spread. Soon other states were calling. Five years later, Cadora's maps are well-known in criminal-justice circles. He now works at the After-Prison Initiative, a program of the George Soros-funded Open Society Institute, and demand for his maps continues to grow. By now, he and Swartz have made maps for agencies in Rhode Island, Florida, Arizona, Connecticut, Louisiana, Kentucky, and New Jersey. The money that taxpayers spend on prisons pays for the incarceration of some very violent people-the sorts of criminals who neighbors are eager to see go away. These dollars are also used to lock up individuals who commit nonviolent crimes-possession of a few vials of crack, for example. Soon these individuals will be released from prison, and they'll go back to the same neighborhoods. Statistics show there is a strong likelihood they will be locked up again. Professor Clear, who has worked closely with Cadora, says the maps suggest a different sort of solution: "Use some of that money to improve the places those people came from in the first place, so that they are not crime-production neighborhoods." This might sound like a fantasy scenario-and a few years ago, that's all it really was. Just a radical idea, to which Cadora and a colleague gave a wonkish name: "justice reinvestment." But budget shortfalls have a way of encouraging politicians to re-evaluate even the most popular policies, and many states have concluded that they simply cannot afford to keep so many people in prison. For the most part, states that have shrunk their inmate populations have then steered the savings into a general fund. One state, however, has reinvested in the neighborhoods that are home to the bulk of its prisoners. Until recently, Connecticut had a $500 million budget deficit and more prisoners than it could house. State Representative Michael P. Lawlor, a Democrat from East Haven, joined with fellow legislators in 2003 to introduce a bill that would scale down the inmate population and funnel the savings into social programs. To win over their colleagues, the legislators invited Cadora to present his maps. "A picture is worth a thousand words," says Lawlor, a former prosecutor who chairs the Judiciary Committee. "I think Eric is able to graphically depict the insanity of our current system for preventing crimes in certain neighborhoods. We're spending all of this money and not getting very good results. I think when you look at it the way Eric is able to depict it in those neighborhood graphs, you can see how crazy this all is." Connecticut legislators passed the bill this spring. To shrink the prison population, they adopted several strategies, including reducing the number of people sent to prison for violating probation rules. And they steered the savings into services designed to curb recidivism, including mental-health care and drug treatment. Programs in New Haven-which has many high-incarceration neighborhoods-will receive $2.5 million. "It's a huge precedent, even though it's a small state," says Michael Jacobson, former commissioner of the New York City Department of Correction, who worked as a consultant for the Connecticut legislature and wrote about the experience in his forthcoming book, Downsizing Prisons: How to Reduce Crime and End Mass Incarceration. "It's the first state that through legislation has simultaneously done a bunch of things that will intelligently lower its prison population, and then reinvest a significant portion of that savings in the kind of things that will keep lowering its prison population. No other state has done anything like that." The idea may be starting to catch on. In Louisiana, three state senators introduced a bill earlier this year that proposed to trim the prison population, save more than $3 million a year, and then spend that savings on helping ex-prisoners find jobs. The bill did not pass, but the idea caught the attention of Governor Kathleen Babineaux Blanco, a Democrat, whose state has the highest rate of incarceration in the country. She invited representatives of three foundations, including Cadora, to a luncheon at the governor's mansion. At the request of her office, Cadora will be creating many more detailed maps of Louisiana. New York's situation is slightly different from those of Louisiana and Connecticut. While the national prison population continues to rise, New York's inmate population has actually been dropping, from a high of 71,538 inmates in December 1999 to fewer than 65,000 today. Without overcrowded prisons-and without a budget crisis like the one Connecticut was facing-there isn't the same sense of urgency in the state legislature. This past spring, State Senator Velmanette Montgomery, a Brooklyn Democrat, introduced a bill to establish the New York State Justice Reinvestment Fund, a $10 million pilot program to finance organizations that assist ex-prisoners. Though the bill has 10 co-sponsors, its prospects of passing in the Republican-controlled senate are slim. The state assembly included a provision in its drug-law reform bill this year to commission more prison-spending maps, but that bill didn't pass the senate either. A map of million-dollar blocks, with stark concentrations of color, can quickly convey a sense of how self-defeating many criminal-justice policies have become-how, for example, spending exorbitant amounts of money locking people up means there's far less money available for programs that decrease crime, like education, drug treatment, mental-health care, and job training. But these maps don't tell the whole story, since they don't show what happens after inmates are set free. New York's state prisons release around 28,000 people a year. Nearly two-thirds of them return to New York City. They arrive wearing state-issued clothes-a plain sweatshirt and stiff denim pants-and they come back to the same streets they left. They bring home all the memories and lessons of prison life, plus the system's parting gift, $40. Usually, they discover that the neighborhoods they left behind have not changed, and that life on the outside can be incredibly difficult. If the past is any predictor, 40 percent of them will be back upstate within three years.

The Making of the MapHow much does it cost to keep somebody locked up? This map, created by Eric Cadora and Charles Swartz, illustrates the estimated cost per block for people who entered the state prison system in 2003. To make the map, Cadora and Swartz obtained home addresses and prison sentences -- like three to six years -- for everyone who was sent to prison in 2003. Then they took each person's minimum sentence (in the above example, that would be three years) and multiplied that number by $30,000 in order to figure out what the total expense will be for his or her incarceration. The estimates shown on this map are conservative. Many inmates remain in prison longer than their minimum sentence. And the figure of $30,000 may be lower than the actual cost per year to hold an inmate in a New York State prison. (The state Department of Correctional Services puts this number at $26,933, but a recent report from the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics gives it as $36,835.) In addition, this map features only prison costs -- not jail costs. Prisons hold people who have been convicted of a crime; jails, like those on Rikers Island, are for people who have been accused of a crime and are not yet convicted, or for people who have received sentences of one year or less. The darkest red areas on this map are "million-dollar blocks" -- blocks where so many people were sent to prison in 2003 that the total cost of their incarceration will exceed a million dollars. There would have been many more "million-dollar blocks" if jail expenses were factored in. And the price tag per block would climb even higher if other criminal-justice costs -- like those for probation and parole -- were also added. As it is, in 2003, there were 35 million-dollar blocks in Brooklyn, out of a total of 9,589 blocks. |

|

For the latest drug war news, visit our friends and allies below We are careful not to duplicate the efforts of other organizations, and as a grassroots coalition of prisoners and social reformers, our resources (time and money) are limited. The vast expertise and scope of the various drug reform organizations will enable you to stay informed on the ever-changing, many-faceted aspects of the movement. Our colleagues in reform also give the latest drug war news. Please check their websites often. |

|

|

|