Getting Real About Real Offense Guideline Sentencing

A goodly number of people reading this ‘blog’ have a loved one serving time in federal prison, and doing a goodly portion of time on “Real Offense” — not Charged Offense. I remember expecting to hear that my brother was receiving a mandatory minimum of eight years. I thought when that moment came, I’d dissolve. When the judge said 330 months, my mom looked at me confused, I did some quick math, and she nearly died on the spot.

How did eight years, even his attorney thought would be eight or nine years, become more than 27 years in federal prison? Years later, a juror asked me how that happened, too -- and when the juror found out some of the details of 'so-called witnesses' -- the juror filed an affidavit with the sentencing judge. It would take me awhile to understand that the reason was an entirely new federal sentencing system, and a provision within it, a brand new Sentencing Commission dubbed “Relevant Conduct”, a new legal provision and term that would drive “Real Offense Sentencing Guidelines.”

With new federalized crimes––specifically drug, fraud, and firearms offenses––quantity-driven or ‘aggregatable offenses’ (the amount of drugs involved, money defrauded, or firearms seized) determine the sentence. Drug cases differ in that the amount of drugs, or combination of drugs, don’t have to be proven at trial, or admitted to in a plea bargain, and goes even further to look at a defendants' complete life's history, and much more!

If a jury says ‘not guilty,’ the judge can and does sentence the accused to that crime nonetheless. The prosecutor holds discretionary power. A defendant can plead guilty to one set of charges, and be sentenced to a whole string of others. The

United States Sentencing Commission's 15-Year Assessment, admits that "The relevant conduct rule has been called the "cornerstone" of the guidelines system, and also say that "sentence begins at investigation." (Part I, Pages 16-77 are of particular interest to this subject).

To this day, I don’t think people realize how many years in prison people are serving for the very ‘crimes’ the juries didn’t feel the prosecutor proved, or crimes people "took responsibility" for.

How many years are being served for ‘acquitted conduct’ that shows up on the “Pre-Investigation Report?” And why didn’t fraud cases soar, or firearms, when these changes of law were made in the 80’s? Does corporate fraud devastate entire communities? Ask those folks living in the communities around ENRON headquarters if fraud is devastating. Ask ENRON shareholders?

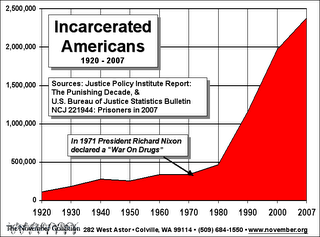

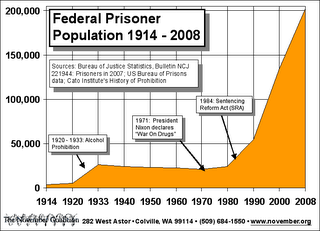

Why did only drug imprisonment soar?

Only drug imprisonment soared because the corporations didn’t let the federal government go very far during the grid-making process of sentencing, or earlier investigative processes either - the policing end. Business pressured the Commission to ‘back-off’. Back off whom? Executives, CEO’s of large and wealthy corporations. There’s

research on that subject available for a fee, wherein Rodriguez and Barlow show how business groups pressured members of the Commission to eliminate or minimize legal sanctions.

The big, brand new sentencing system that experts still crow about as “Modern Sentencing” is still bad 30 years later. And it’s still punishing the non-violent drug offender the most. One look at this incarceration chart — my imagination soars —

doesn’t it look like ‘the finger’? Yeah, the non-rich are certainly ‘getting the finger’ these days.

David Yellen of Loyola University (Chicago) School of Law put forth an interesting paper entitled:

Reforming the Federal Sentencing Guidelines’ Misguided Approach To Real-Offense Sentencing. Yellen is astute, and very politely discusses this vitally important issue.

Aside from studying legal papers into the night, I watch entertainment TV if a story appears compelling. Watching NBC's Dateline the other night and saw the story about the couple who went out with a dive-boat to explore the Great Barrier Reef. Left behind by the boat’s crew, they spent an evening, night and terrified dawn drifting in the open ocean before a miraculous rescue came. Both of them were terrified they were going to be attacked by sharks, but neither would say the “S” word. To say the “S” word would take them over the top of terrified, unable to cope with their terrible predicament.

Writers and critics of Relevant Offense within Real Offense Sentencing Guidelines are sort of like the couple in the ocean. We have the “S” word there, too. Not unlike sharks in their power to devour, they’re called snitches, to be precise, and for best purpose, called the 'Rewarded Informant" today. Their tales show up in police offices through various means. Some people are out of work and know the police pay for ‘information from the streets.’ A person can make a regular living at it. Other rewarded informants appear in the form of a friend, the one who gets caught first, or an acquaintance who gets caught and won’t "rat-out" his friends. A friend of the friend, from years ago,

fingers you, and rewarded words are believed by the prosecutor and/or the authority who writes and influences the Pre-Sentence Investigation Report that includes a calculation of federal prison time that must be served.

The sharks of the drug war show up before sentencing. The rewarded informants' words, show up to convince judges to allow militarized police to carry out a no-knock drug raid. They show up at the grand jury, and trial, and the government calls them ‘witnesses.’ They show up at sentencing for the relevant conduct story that puts the convicted or plead-out person into the "Real Offense Sentencing Guideline," and that's where a defendant really gets nailed.

What’s eating us, or might eat you, needs to be talked about, and outside of academic circles. Okay, we can't say the "S" word, but we certainly can talk about the troublesome informant system. Looking hard at relevant conduct, we come smack in the face of rewarded "testimony" via the informant — not proven before a jury to be true — but proven to add more years than most charged offenses do. That’s not justice.

I attended the Second Roundtable, convened by the ACLU, to explore how to make changes in law to correct some abuses within a legal system dependent on

desperate informants to ‘solve crimes.’ Davy-D, a father of the hip-hop social change movement, was there, and at one point lamenting that we’d been on the defensive since people ‘on the street’ began to teach about the workings of the informant system––and the threat to public safety and social order that such a bad policing system is.

Leading fellow citizens down the road to greater understanding of the Federal Sentencing System, including Real Offense Sentencing Guidelines, is one way to find some high ground on the slippery issue of informants and policing; informants and prosecutors; informants and the sentencing judge, and informants on our society entire.

Now readers, beyond difficult legal papers on the problem — what are your ideas about ‘translating’ difficult concepts of law for the average person-on-your-streets? Or do you have a question? We're listening. Send us email, or leave a public comment by selecting the comment link below.

In Struggle,

Nora

___

Labels: Federal Guideline Sentencing, Informant System, Real Offense, Relevant Conduct, US Sentencing Guidelines